An Introduction from Selim Jahan, Director of the Human Development Report Office and Lead Author of the report

Chapter 1: Work and human development–analytical links

Work is intrinsic to human development. From a human development perspective, the notion of work is broader and deeper than that of jobs or employment alone. The jobs framework fails to capture many kinds of work that are important to human development—such as unpaid care work, voluntary work and such creative work such as writing or painting. Through this lens the report identifies ways to strengthen the link between work and human development.

The interactive visualization below explores the synergetic relationship of work and human development. Hovering over or clicking different elements with an input device will activate interactive content.

Work enhances human development, but some work damages human development and some work puts workers at risk.

When positive, work provides benefits beyond material wealth and fosters community, knowledge, strengthens dignity and inclusion. Nearly a billion workers in agriculture, 450 million entrepreneurs, 80 million workers in health and education, 53 million domestic workers, 970 million voluntary workers contribute to human progress.

When negative, in the form of forced labour, child labour and human trafficking, work can violate human rights, threaten freedom and shatter dignity. An estimated 21 million people are currently in forced labour of whom 14 million (67 percent) were exploited for labour and 4.5 million (22 percent) sexually exploited. There are still 168 million child labourers worldwide. And some work e.g. work in hazardous industries may put workers in risk. There are 30 million workers in mining and their face risks every day.

Over the years work has contributed considerably to impressive progress in human development. However the progress has been uneven with significant human deprivations and large human potentials remain unused.

The chapter feature special contributions by Kailash Satyarthi, Activist and 2014 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and Lemayh Gbowee, Peace Activist and 2011 Nobel Peace Prize winner.

Human development

Human development is a process of enlarging people’s choices—as they acquire more capabilities and enjoy more opportunities to use those capabilities to enhance well-being.

Human development implies that people are not only beneficiaries of development, but must influence the process that shapes their lives.

In all this, economic growth is an important means to human development, but not the goal. And there is no automatic link between economic growth and human development.

Work

For this report, work is defined as any activity that not only leads to the production and consumption of goods or services, but also goes beyond production for economic valuejobs and employment, but also unpaid care work, voluntary work and creative expressions. Work thus includes activities that may result in broader human well-being, both for the present and for the future generations.

Human development is affected by work through many channels

Income and livelihood. People work primarily to achieve a decent standard of living. In market-based economies they generally do so through wage or self-employment.

Security. Through work people can build a secure basis for their and their families’ lives, enabling them to make long-term decisions and establish priorities and choices.

Women’s empowerment. Women who earn income from work often achieve greater economic autonomy and decision-making power within families and communities.

Participation and voice. By interacting with others through work, people learn to participate in collective decision-making and gain a voice.

Dignity and recognition. Good work is recognized by co-workers, peers and others and provides a sense of accomplishment, self-respect and social identity.

Creativity and innovation. Work unleashes human creativity and has generated countless innovations that have revolutionized many aspects of human life—as in health, education, communications and environmental sustainability.

Workers can also benefit from higher human development, again operating through multiple channels

Health. Healthier workers have longer and more productive working lives and can explore more options at home and abroad.

Knowledge and skills. Better educated and trained workers can do more diverse work—and to a higher standard—and be more creative and innovative.

Awareness. Workers who can participate more fully in their communities will be able to negotiate at work for better conditions and higher labour standards, which in turn will make industries more efficient and competitive.

Chapter 2: Human development and work: progress and challenges

Over the past two decades, the world has made major strides in human development. Today, people are living longer, more children are going to school and more people have access to clean water and basic sanitation.

Since 1990, 2 billion people have been lifted out of low human development, extreme income poverty has been reduced by more than a billion. Every region of the world has seen Human Development Index (HDI) gains.

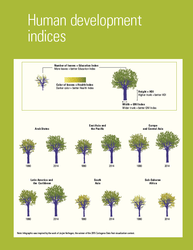

The interactive visualization below explores changes in HDI and its components on country, region and global levels. To create and compare “HDI trees” of any two countries or regions using data from 1990 or 2014, please press “change” and follow the instructions.

The visual legend can be accessed on the right. The height of a tree trunk represents HDI (higher trunk = better HDI); width of a tree trunk represents GNI Index (wider trunk = better GNI Index); number of leaves represents Education Index (more leaves = better Education Index); and color of leaves represents Health Index (greener leaves = better Health Index).

Change

Select a country, region or development classification for this tree to compare the results

Change

Select a country, region or development classification for this tree to compare the results

Change

Select a country, region or development classification for this tree to compare the results

The human progress has been contributed to by the work of nearly 1 billion people in agriculture, the contributions of 80 million workers in health and education, the creativity of 450 million entrepreneurs and the support of 53 million of domestic workers.

At the same time, human progress has been uneven with deep human deprivations. And significant human potential remains unused, misused and abused. More than 200 million people with 74 million young people are out of work, more than 800 million working poor are living on less than $2 a day.

Overcoming the existing human deprivations and addressing the emerging human development challenges will require optimal use of the world’s human potential.

The chapter features special contribution by Robert Reich, Former United States Secretary of Labor.

Chapter 3: The changing world of work

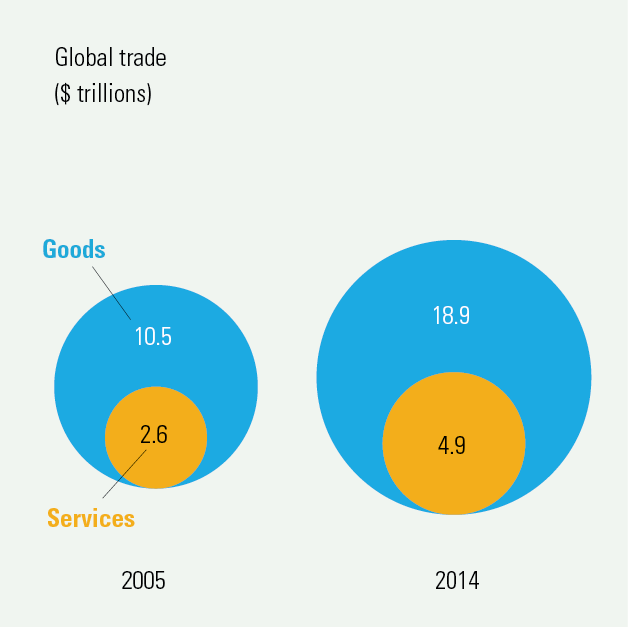

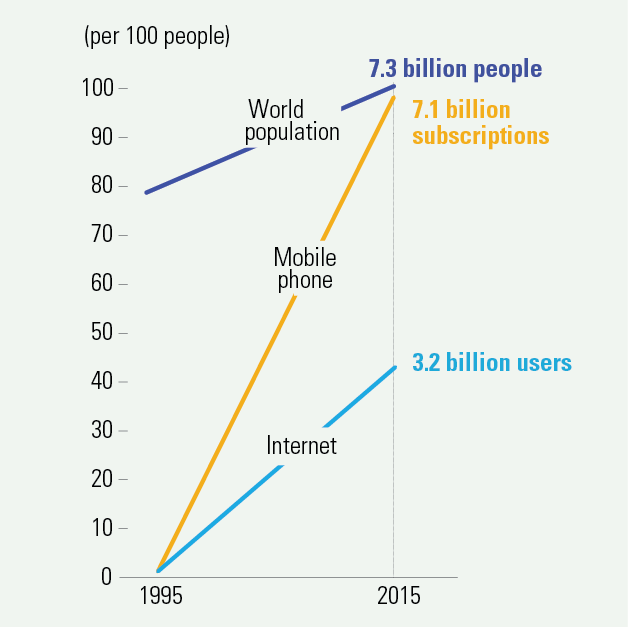

Today, the transformation of work is driven by globalization and technological revolutions, particularly the digital revolution. Globalization has fostered global interdependence, with major impacts on patterns of trade, investment, growth and job creation and destruction—as well as on networks for creative and volunteer work. We seem to be living through new and accelerated technological revolutions. New opportunities are emerging, but so do new risks. In this new world of work there are winners, so are losers and human development impacts mixed.

Chapter 4: Imbalances in paid and unpaid work

In 2015 the global labour force participation rate was 50 percent for women but 77 percent for men. Worldwide in 2015, 72 percent of working-age men were employed, compared with only 47 percent of women. Female participation in the labour force and employment rates are heavily affected by economic, social and cultural issues and care work distributions at home.

Analyses of total hours worked in time-use surveys (in a sample representing 69 percent of the global adult population), shows that women contribute 52 percent of global work to men’s 48 percent. Even though, women carry out the major share of global work, they face disadvantage in the world of work, both in paid and unpaid work.

The interactive visualization below explores imbalances in paid and unpaid work using the time-use survey data from 63 countries.

Men dominate the world of paid work, women the world of unpaid work. Of the 59 percent of work that is paid, mostly outside the home, men’s share is nearly twice that of women—38 percent versus 21 percent. The picture is reversed for unpaid work, mostly within the home and encompassing a range of care responsibilities: of the 41 percent of work that is unpaid, women perform three times more than men—31 percent versus 10 percent.

In the realm of paid work, women are engaged in the workforce less than men, their work tends to be more vulnerable (globally half of employed women are in vulnerable jobs) and they are under-represented in senior management (in businesses, women represent only 22 percent of senior managers.), reinforcing disadvantages. In the realm of unpaid work, women share more of the care burden (undertaking more childcare, care for elders and those with disabilities), which limits their options, discretionary free time and access to social pensions.

The report calls for reducing the burden of unpaid care work, expanding opportunities for women to engage in paid work. Outcomes could be improved by equal pay, flexible work, greater social protection, parental leave and addressing harassment and social norms that exclude women from work. There is also a need for valuing unpaid care work for advocacy and policy purposes.

The chapter features special contribution by Roza Otunbayeva, Former President of Kyrgyzstan.

Chapter 5: Moving to sustainable work

Sustainable work refers to work that promotes human development while ensuring sustainability. It is critical not only for sustaining the planet, but also for ensuring work for future generations.

Some occupations can be expected to loom larger—railway technicians, for instance, as countries invest in mass transit systems. Terminated workers may predominate in sectors that draw heavily on natural resources or emit greenhouse gases or other pollutants. About 50 million people are employed globally in such sectors (7 million in coal mining, for example).

For sustainable work to become more widely prevalent, three developments are needed in parallel: termination, transformation and creation, each requiring specific actions by national and international policymakers, industry and other private sector actors, civil society and individuals.

Infographic below explains effects of work on environmental sustainability and human development.

Sustainable work (in the top-right square of the matrix in the infographic) takes place in developed and developing economies, but it can differ in scale, in the conditions of work, in the links to human development and in the implications for policy.

- Termination. Some existing work will have to end, and the workers displaced will need to be accommodated in other occupations (bottom-left square of the matrix in the infographic).

- Transformation. Some existing work will need to be transformed in order to be preserved through a combination of investment in adaptable new technologies and retraining or skill upgrading (top-left and bottom-right).

- Creation. Some work will be largely novel, benefiting both sustainability and human development, but will emerge from outside the current set of occupations (top-right square of the matrix in the infographic).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have implications for sustainable work and sustainable work is also critical for achieving the SDGs. SDG with the most direct implications for sustainable work is goal 8 (promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all), and its associated targets which spell out some of the implications for sustainable work.

Target 8.7, for example, is to take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including the recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms.

Target 8.8—to protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment—aims to strengthen the human development outcomes of workers, avoiding a race to the bottom.

Similarly, sustainable work is also crucial for achieving the SDGs as it contributes to poverty elimination, ending hunger, promoting sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth and so on.

The chapter features special contributions by Maithripala Sirisena, President of Sri Lanka and Nohra Padilla, Director of the National Association of Recyclers (Colombia) and of the Association of Recyclers of Bogota, Recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2013.

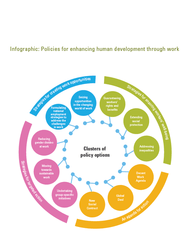

Chapter 6: Enhancing human development through work

Policy options for enhancing human development through work have to be built around three broad clusters: (1) creating more work opportunities to expand work choices, (2) ensuring workers’ well-being to reinforce a positive link between work and human development and (3) targeted actions to address the challenges of specific groups and contexts. An agenda for action to build momentum for change is also needed pursuing a three-pillar approach—a New Social Contract, a Global Deal and the Decent Work Agenda.

The interactive visualization below explores clusters of policy recommendations. Hovering over or clicking different elements with an input device will activate interactive content.

Strategies for ensuring worker well-being must focus on rights, benefits, social protection and inequalities

Guaranteeing the rights and benefits of workers is at the heart of strengthening the positive link between work and human development and weakening the negative connections. Policies could include

Setting legislation and regulation

Ensuring that people with disabilities can work

Making workers’ rights and safety a cross-border issue

Promoting collective action and trade unionism

Only 27 percent of the world’s population is covered by comprehensive social protection which severely limits the security and choices of workers. Action to extend social protection should focus on

Pursuing well designed, targeted and run programmes

Combining social protection with appropriate work strategies

Assuring a living income

Tailoring successful social protection programmes to local contexts

Undertaking direct employment guarantee programmes

Targeting interventions for older people

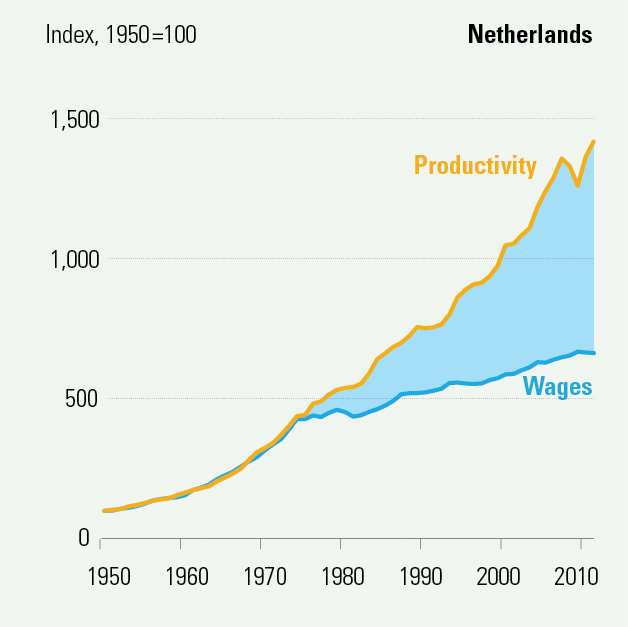

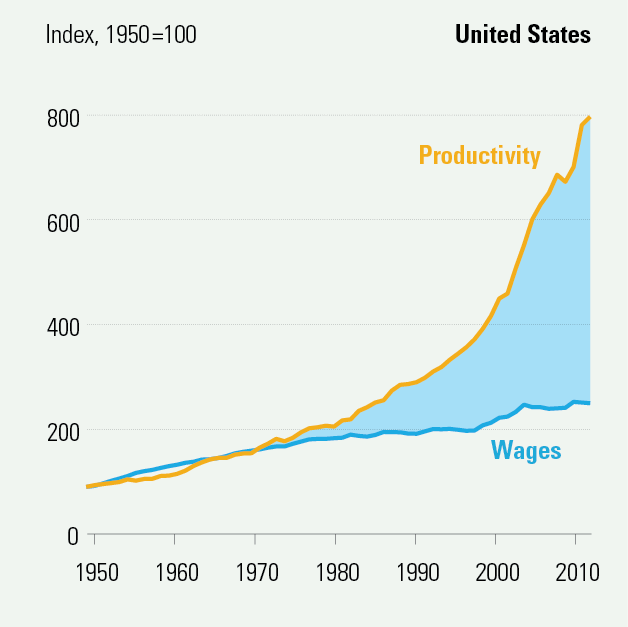

Because workers are getting a smaller share of total income and inequalities in opportunities are still substantial, policy options should focus on

Formulating and implementing pro-poor growth strategies

Providing complementary support

Democratizing education, particularly at the tertiary level, nationally and globally

Pursuing profit sharing and employee ownership

Adopting and enforcing proper distributive policies

Regulating the financial sector to reduce the regressive effects of cycles

Removing asymmetries between the mobility of labour and of capital

Developing a new social contract

In the new world of work participants are less likely to have long-term ties to a single employer or to be a member of a trade union than their forebears. This world of work does not fit the traditional arrangements for protection. There may be a need for a new social contract in such circumstances involving dialogue on a much larger scale than took place during the twentieth century

Beyond the policy options, a broader agenda for action is needed

Pursuing a global deal

A global deal would require mobilizing all partners—workers, businesses and governments—around the world, respecting workers’ rights in practice and being prepared to negotiate agreements at all levels. This will not require new institutions, merely reoriented attention in the world’s strong international forums

A global deal can guide governments in implementing policies to meet the needs of their citizens. Without global agreements, national policies may respond to labour demands at home without accounting for externalities

Implementing the Decent Work Agenda (four pillars)

Employment creation and enterprise development

Standards and rights at work

Social protection

Governance and social dialogue

Balancing paid and unpaid work opportunities between women and men may benefit from the following policy measures

Expanding and strengthening gender-sensitive policies for female wage employment

Actions to increase representation of women in senior decisionmaking positions

Specific interventions

Focusing on maternal and paternal parental leave

Enlarging care options, including day-care centres, after-school programmes, senior citizens’ homes and long-term care facilities

Encouraging flexible working arrangements, including telecommuting

Valuing care work

Gathering better data on paid and unpaid work

Targeted actions are needed for balancing care and paid work, making work sustainable, addressing youth unemployment, encouraging creative and voluntary work and providing work in conflict and post-conflict situations

Targeted measures for sustainable work may focus on terminating, transforming and creating work to advance human development and environmental sustainability. Policy measures may focus on

Adopting different technologies and encouraging new investments

Incentivizing individual action and guarding against inequality

Managing trade-offs

Mechanism to translate the desired global outcomes into country actions

Undertaking group-specific initiatives

Initiatives for young people

Providing policy support to the sectors and entities creating new lines of work

Investing in skills development, creativity and problem solving

Providing supportive government policies to help young entrepreneurs, etc.

Initiatives for creative work

Innovating inclusively

Assuring democratic creativity

Funding experimentation and risk, etc.

Initiatives in conflict and post-conflict situations

Supporting work in the health system

Getting basic social services up and running

Initiating public works programmes

Formulating and implementing targeted community-based programmes

Seizing opportunities in the changing world of work requires policy actions to help people thrive in the new work environment

Heading off a race to the bottom

Providing workers with new skills and education

Formulating national employment strategies to address crisis in work

Setting an employment target

Formulating an employment-led growth strategy

Moving to financial inclusion

Building a supportive macroeconomic framework

Strategies for creating work opportunities requires well formulated employment plans as well as strategies to seize opportunities in the changing world of work

Societies can turn challenges caused by changes in the world of work into opportunities that would enhance human development. The report recommends work which enables people to find employment opportunities without damaging prospects for future generations. The report suggests investing in energy efficient technologies, prioritising ethical consumption and investment and enhancing skills development, creativity, entrepreneurship and problem solving among a workforce. The Report also calls for national employment strategies, dual targeting by central banks, employment-led growth rather growth-lead growth strategies, a living income and profit sharing by workers.

The chapter features special contribution by Benigno S. Aquino III, President of the Philippines.

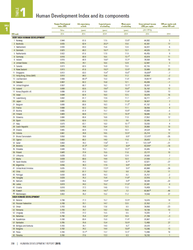

Statistical annex

The report features 16 statistical tables in the annex as well as the statistical tables following chapters 2, 4 and 6 provide an overview of key aspects of human development. The first seven tables contain the family of composite human development indices and their components estimated by the HDRO. The remaining tables present a broader set of indicators related to human development.

Unless otherwise specified in the notes, tables use data available to the HDRO as of 15 April 2015. All indices and indicators, along with technical notes on the calculation of composite indices and additional source information, are available online at http://hdr.undp.org/en/data.

Countries and territories are ranked by 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) value. Robustness and reliability analysis has shown that for most countries the differences in HDI are not statistically significant at the fourth decimal place. For this reason countries with the same HDI value at three decimal places are listed with tied ranks.